Is "acceptably non-dystopian" self-sovereign identity even possible?

Anonymity and trustlessness are central to the crypto world. People don’t have to attach real-world identities to crypto wallets, and communities at least nominally try to avoid placing trust into institutions like governments or big tech companies. But with the crypto world increasingly trying to move beyond simple payments and NFT trades, they are running up against these limitations.

Decentralized autonomous organizations, or DAOs, are often governed with a “one token, one vote” model that gives power to the wealthy. Though some DAOs may believe this is the ideal governance model, many others have adopted it because there aren’t a ton of promising alternatives. Unlike in offline organizations and societies where centrally-controlled identifiers or even just in-person attendance are fairly successfully used to ensure one individual gets one vote, this has been a very difficult nut to crack in the crypto world, where one individual can trivially create endless new wallet addresses—known as a Sybil attack.1

Loans in the crypto world tend to be overcollateralized, requiring users to put up more value in crypto than what they receive in a loan. Although this works reasonably well for users who have already accumulated capital and want to use that capital in a different format (i.e. borrowing fiat currency against their crypto holdings), it doesn’t work well for the more standard reason people take out loans: because they don’t already have the money they need. Needless to say in an ecosystem whose advocates like to promise will “bank the unbanked” and help the marginalized, this is a bit of a setback. The need for these overcollateralized loans again stems from a lack of indicators to a person’s trustworthiness like those that are used in traditional finance, such as credit scores or banking records. Overcollateralized crypto loans are also made even more necessary on some anonymity-preserving loan platforms that choose not to require know-your-customer (KYC), who otherwise would see an influx of anonymous users borrowing money and making off with it.

So, increasingly, we’re seeing conversations around topics like: how can we verify a statement about a person (or crypto wallet) is true without relying on the state or another centralized entity? How can we ensure that a wallet represents a unique individual?

Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin has been talking about “soulbound tokens”.2 Jack Dorsey just launched “Web5”, a buzzwordy project focused on decentralized identity.3 Projects like Proof of Humanity,4 BrightID,5 and WorldCoin6 are all tackling Sybil prevention in their own ways. Web3 companies like Spruce7 and Disco8 have emerged to try to tackle self-sovereign identity (that is, identifiers that are controlled by users rather than by central entities) in the blockchain world and elsewhere.

Contents

- Some context

- Concepts

- The trilemma of digital identity

- Proof of personhood

- Verifiable attestations

- Soulbound tokens and negative attestations

- Verifiable credentials

- Data custody and security

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

Some context

Self-sovereign identity is not a new concept, nor are the problems crypto is facing around online identity unique to crypto. Some of the solutions that have been discussed recently don’t necessarily involve blockchains, and are broad approaches to digital identity.

I’ve had opinions on and concerns about issues pertaining to online identity and credentials long before I started researching crypto, and most of my opinions on this topic apply regardless of whether blockchains are involved or not. But there has been a resurgence of interest in self-sovereign identity because of crypto and web3, and that has motivated this essay.

Self-sovereign identity is one of those things that sounds wonderful at a glance, but can get pretty dystopian the more you start to think about it. Conversely, centrally-controlled identifiers left to governments and corporations have their own obvious and serious issues particularly when it comes to marginalized groups, oppressive governments, and access. This essay is not intended to describe self-sovereign identity and related topics as universally bad or universally good, but rather to raise some issues that I think desperately need to be considered as people are working on these problems.

The technology industry, and the crypto industry especially, has long adopted a “move fast, break things” approach to innovation. Companies and developers have sacrificed quality, security, and user safety in the name of innovation, writing off collateral damage to real human beings as simply a cost of progress. Considerations of ethics, user safety, privacy, security, “how can this be used for evil”, and “is this even good for society” often come as a belated afterthought, and “testing in production” is the norm. Regulators and legislators lag behind, often only intervening once enormous harm has been done (and often not even then).

Self-sovereign identity is not a field where “move fast, break things” is acceptable. People are already talking about capturing enormously sensitive information in digital form, issuing attestations about other individuals either with or without their consent, and, in some cases, recording all of these things to immutable blockchains where they would be stored indefinitely. This terrifies me.

Concepts

- Decentralized identifiers (DIDs): a proposed recommendation9 for unique identifiers that provably belong to an individual or organization. These can represent various concepts: a person might have multiple DIDs representing identifiers like their Ethereum address, their email address, their driver’s license number, or their national ID number. Similarly, an organization might have DIDs representing their phone number or their employer identification number. These can be issued by the individual or a third party (for example, a government might issue the DID representing a national ID number), and the identity of the issuer and the recipient can be cryptographically proven. These DIDs are used to sign verifiable credentials.

- Proof of personhood: a means of establishing that an identity like a wallet address corresponds to a unique individual in a network. This is also sometimes called “proof of humanity”, though that term also describes a specific organization implementing one approach to PoP.

- Self-sovereign identity: the general term for an approach to online identity that is controlled by the user, rather than maintained by a central party.

- Soulbound tokens: Vitalik Buterin and a group of others have been recently working on the idea of “soulbound tokens”: non-transferable, unique tokens much like NFTs that are bound to “souls” belonging to unique individuals. They describe these being used to represent concepts like birth certificates or college diplomas, which unlike NFTs should not be transferable.

- Verifiable credentials: a recommendation10 describing how digital credentials can be issued and proven. Someone might have a verifiable credential that represents things that we might normally think of when we think of “credentials”: say, a college diploma, professional certification, or security clearance. But these can also be used to certify other things: proof that someone completed a course and earned a given grade, or attended a specific event, or purchased an item, or became a member of an organization. Someone could even issue a verifiable credential to describe themselves: for example, they could state their favorite color via VC.

The trilemma of digital identity

Trilemmas are a set of three goals, where all three are not simultaneously achievable.

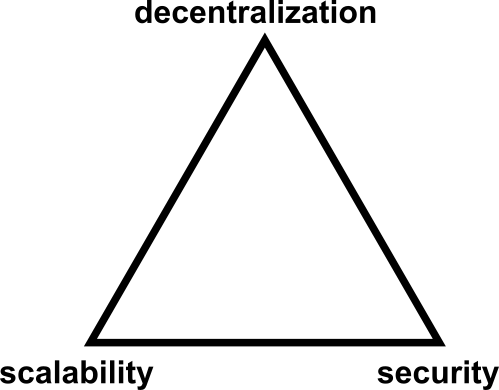

Some crypto-literate readers will already be familiar with the blockchain trilemma: decentralization, scalability, and security. Blockchains end up making tradeoffs in one goal to achieve the other two (though there are those who argue all three can be achieved, but that’s another subject entirely).

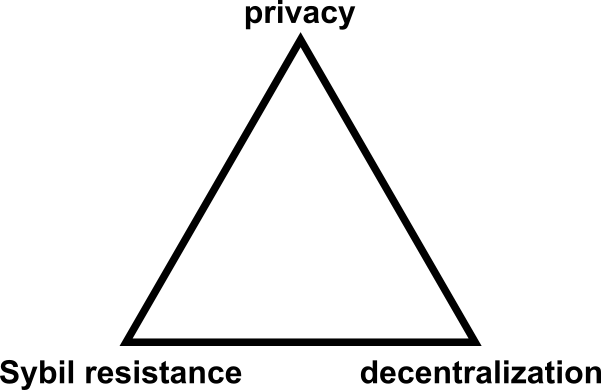

Digital identity has its own trilemma: privacy, Sybil resistance, and decentralization.11

Today’s blockchain ecosystems almost universally sacrifice Sybil resistance for decentralization and privacy. But increasingly, people are trying to tackle the problem of Sybil resistance, causing organizations to make trade-offs in decentralization, privacy, or often both.

Bitcoin, Ethereum, and most other cryptocurrency projects don’t rely on a central authority to record identities, and users don’t have to disclose any personal information when they create wallet addresses, but as a result, projects using those addresses as the sole identifiers are vulnerable to Sybil attacks.

Some crypto projects seeking to avoid Sybil attacks require additional KYC checks, where users submit government-issued identification documents to prove their identity. This accomplishes Sybil resistance, but at the expense of privacy and with the added reliance on other forms of identification that are neither privacy-preserving nor decentralized.

Proof of personhood

Proof of personhood is an umbrella term for various attempts to prove that a person is unique within a network, or even unique in the world. They seek to solve the Sybil problem, but so far these projects sacrifice privacy and/or decentralization to varying degrees of dystopianism.

Some might already be familiar with Worldcoin, a Sam Altman brainchild that promises to eventually implement universal basic income. MIT Technology Review6 and BuzzFeed News12 both published excellent investigative articles into the project nearly simultaneously in early April. For those who are not familiar, the project seeks to solve the Sybil problem by requiring users to provide iris scans and various other biometric data by staring into a large chrome orb. Worldcoin would argue that its alpha-stage product is, or at least will eventually be, privacy-preserving, as they intend to store only hashes of the iris data rather than the data itself. Whether or not they are deleting the biometric data as they promise they will (eventually, probably), it’s tough to argue that one could achieve proper anonymity in a system where an “orb operator” interacts with them in person and provides them with a crypto address. It’s certainly not decentralized, with data all being stored in opaque Worldcoin systems. It would also be difficult to describe this approach as self-sovereign in any way—the user has no control over the identity that is created for them and stored on Worldcoin’s system (which certainly would seem to raise some concerns from a GDPR perspective as well). I don’t think the dystopian nature of a company that uses a chrome orb to collect not only iris scans, but high-resolution images of users’ faces and bodies, as well as “contactless doppler radar detection of [their] heartbeat, breathing, and other vital signs”, needs much explaining.6

BrightID is another project aiming to verify “universal proof of uniqueness”. Users join a social graph, attesting to the identities of people they know and trust in real life. The project doesn’t rely on a central entity to maintain the store of information, so it achieves the decentralization goal, but its entire web-of-trust system relies on people revealing their identities to some people within the system. BrightID also reveals a massive web of verifications between users and the level to which they’ve reported knowing one another. With the emergence of Facebook this type of privacy intrusion is perhaps fairly normalized, but it’s certainly a far cry from the “privacy” users often seek and expect from blockchain systems. After all this, BrightID is still vulnerable to Sybil threats: a person simply needs to find disjoint groups of people to each verify new identities. BrightID also incorporates a dystopian “social credit”-style pattern, where not only are users penalized for “bad behavior”, but so too are their connections. According to their documentation: “Some algorithms might take it as a bad signal if your already known connections consider you as someone they have just met or a suspicious connection. Your already known connections’ bad behaviour might also negatively impact your verification.”

Proof of Humanity is quite similar in its approach to BrightID. It adds financial costs to the system, where users must pay (or crowdfund) a deposit to have their profile verified. There’s also a financial “bounty” for users who challenge deceptive profiles. Someone can tell me which dystopian sci-fi novel is based around this premise, because I’m sure it’s already been written. Like Worldcoin, PoH also seeks to implement universal basic income.

Various other systems exist to try to reduce the likelihood of duplicate wallets, if not prevent it outright, in various ways:

In some cases, standard bot-prevention technology like CAPTCHAs is used, not to prevent someone from creating multiple identities in a network but to at least make it annoying to do at scale.

Other systems accumulate massive amounts of data from NFT collections to try to discern the likelihood that a wallet might be a duplicate. For example, proof-of-attendance NFTs (POAP NFTs, often just called POAPs) aim to prove that a person attended a real-life event or experience, and so such systems will take two wallets holding a POAP from the same event to mean they are likely not operated by the same individual. Other NFTs are issued only after the recipient completes a “quest”—some level of participation or effort that is not trivial—and these are used as a signal of uniqueness under the idea that it would be prohibitively difficult for a person to repeat the effort across many wallets.

Some projects dream of a future state where all achievements are represented on-chain, and so they can look at a wallet containing things like a college degree, mortgage loan, and history of attendance at real-world events and presume that one person is not widely duplicating all of these things. Though this might be reasonably Sybil-proof, this is simply not feasible today, and it sacrifices privacy to a horrifying degree.

Verifiable attestations

Much of the recent conversation around digital identity is not focused specifically on the Sybil problem, but instead on verifiable attestations: attestations from one verifiable party about another verifiable party that a statement is true. Though the term “credential” is frequently used by those familiar with W3C’s Verifiable Credentials proposal, the concept might be more accurately described as a “verifiable statement” or “verifiable attestation”. Actual implementations vary, from the W3C’s Verifiable Credentials to Vitalik Buterin’s “soulbound tokens”. For now, I will refer to the broad concept encompassing both of these implementations as “verifiable attestations”.

Proposed use cases for verifiable attestations do encompass what most would think of as “credentials” today: A university might attest that a student earned a given diploma. A government might attest that a person is a citizen. A state might attest that a driver earned their driver’s license. An employer might attest that an employee works for them.

But others have talked about using verifiable attestations more broadly: An event organizer might attest that a concertgoer attended a given concert. A church might attest that an individual is a member of their congregation. A video game developer might attest that a player completed a given level. A brand might attest that a customer bought their product.

The one thing these attestations have in common is that they should not be transferrable: if an entity attests that you earned a diploma or a driver’s license or attended a concert, you shouldn’t be able to transfer that attestation to the highest bidder to claim as though it applied to them.

These attestations, proponents argue, would enable a much more robust level of interaction within the crypto world. These attestations, I argue, sound like a privacy nightmare.

Soulbound tokens and negative attestations

A recent episode of the Bankless podcast featured Vitalik Buterin and Evin McMullen discussing the pros and cons of Buterin’s brainchild, soulbound tokens, and McMullen’s preferred form of attestation, verifiable credentials.

The somewhat dramatic name, “soulbound tokens”, comes from the World of Warcraft concept of soulbound items that can’t be transferred between players. The May 2022 paper he co-wrote with E. Glen Weyl and Puja Ohlhaver describes how the broad idea simply needs to be “acceptably non-dystopian” to be worth pursuing, which seems both like an awfully low bar, and also makes me worry about the definition of “acceptably” they’re going with.

One reason that soulbound tokens (SBTs) are preferable to verifiable credentials, Buterin argues, is that they enable “negative attestations”. He uses loans as an example. Even if you could verify based on someone’s positive attestations that a person met your threshold of trustworthiness to qualify for a $10,000 loan, you would probably also want to verify that they hadn’t already taken out 100 different $10,000 loans from other lenders. Buterin describes this as a “negative” attestation—something that a bad actor might wish to conceal in order to take advantage of a system. In his system, a lender providing a loan could issue an SBT representing the $10,000 debt, and the borrower wouldn’t be able to get rid of that token. When the loan was repaid, the lender would issue a new SBT recording that fact. The borrower, if they tried to go open a new loan, could be required to provide a zero-knowledge proof13 that traversed the set of attestations applying to them on the Ethereum chain, proving they had no open loans (or that they only had below a certain amount of debt outstanding, or some other claim that they could prove based on the tokens they held or didn’t hold).

Now, there are some obvious privacy implications here: not everyone wants to have their debts publicly visible on the Ethereum blockchain. Buterin brushes this off with the argument that such a system could use zk-SNARKs14 to encrypt the token contents as well as its sender and recipient. There are also some edge cases I could poke at with this scenario, around if a lender went out of business or for whatever reason never recorded the repayment. However, compared to what Buterin used as his next example, this scenario was relatively benign. A borrower consented to the “negative” attestation being recorded when they took out the debt, the lender made that a condition of the loan, and any new lenders require proof that the borrower has no loans outstanding. Fine.

The next example Buterin used was negative attestations around criminal records. Uh oh.

In the real world, like in the non-crypto world, there are applications where one side needs to know that the other side is at least reasonably trustworthy. And one thing they might do is prove that the other side doesn’t have a criminal record, right? And that’s nice because it’s like a very simple test that someone is at least not in, you know, the bottom kind of a few percent of trustworthiness probably.15

Now, ignoring Buterin’s more-than-questionable conflation of the lack of a criminal record to trustworthiness, he’s also revealing here that his dreams for soulbound tokens involve police departments uploading criminal records to the blockchain. Not only that, but he’s envisioning a world in which every police department uploads criminal records to a blockchain, providing the level of data completeness required to prove a negative. And finally, he’s envisioning a world where every police department uploads criminal records to his blockchain, the Ethereum blockchain. Although he states elsewhere in the episode that digital identity frameworks would benefit from being system-agnostic and should not require anyone to use a given blockchain (or any blockchain at all), his own dreams for the future clearly don’t involve decentralization except as far as it can be achieved within his preferred blockchain.

Let’s build on the example Buterin so graciously provided. For all the downsides of existing criminal records and background check systems—and there are many, to be sure—there is something to be said for that data being a bit of a pain to access. In today’s world, there is both a financial and time cost for non-law enforcement bodies to check criminal records. I can think of two instances where it’s happened to me: for employment screening, and for a volunteer position where I would be working directly with children. But in a world where all criminal history is recorded on the blockchain, and the proof of a lack of criminal history is quickly and cheaply achieved with a straightforward ZK proof, those barriers are removed. In the name of safety and trust, any DAO, club, or other community could require this proof to join. Those providing tickets to social events or professional conferences could require it. Games and metaverse experiences could even require this before a person is allowed access—after all, what’s the real difference between volunteering with children and potentially interacting with a child in the metaverse? And while those who have not broken the law in the past, or who have the luck, privilege, or financial means to escape their transgressions being recorded, may not balk to being required to submit proof of a clear record for even trivial applications, this normalization would serve to widen the gulf between the convicted and the not-convicted, a gulf that already exists in society and disproportionately impacts marginalized groups.

Buterin’s criminal records vision also exposes his intent for people to be able to send soulbound tokens without the consent of the recipient—given that it is unlikely people would consent to police departments recording their crimes for others to later use against them if they had the choice. This is perhaps an unsurprising vision of Buterin’s, given that the current state of the Ethereum blockchain enables people to send NFTs without the receiver’s consent, a horrifying state of affairs for anyone who’s given more than about ten seconds of thought to the enormous abuse potential. However, this already bad state of affairs is now compounded by the fact that users would never be able to get rid of these SBTs, even if they contained content like doxxing, revenge porn, or child sexual abuse material.

Verifiable credentials

The system of verifiable credentials Disco’s Evin McMullen waxes poetic about on Bankless seems at least preferable to soulbound tokens. The data isn’t stored on-chain, there is consent required before a party can issue a token to you, and negative attestations (and the enormous amounts of on-chain data required for them) aren’t a part of the vision. But to hear her speak of her goals with her Disco product is like watching someone act out the privacy paradox right in front of you.16 Web3 advocates, McMullen included, regularly speak of privacy, anonymity, and data ownership as a top priority. But she also says in an episode of Digitally Rare:

We can’t have fun together in the metaverse if the only thing I know about you is how much money you have. But we can have so much more fun together if I know the friends we have in common, the activities that we both like to enjoy, I know the incredible skillsets that Jonathan and Matt are good at, and I know the kind of music they like to enjoy, the kinds of parties they go to, or even, you know, from a very simplistic perspective: if we want our DAOs to be more than group chats with bank accounts, we need to know enough about one another to solve more interesting coordination problems than treasury allocation. So, if we want to, you know, write a song together, we have to know which one of us knows how to write music! Because a song that’s designed by the richest people in the room might not sound like a great song.17

Her descriptions of this future world, where relationships are front-run by a deluge of data rather than formed more organically between individuals, are enormously reminiscient of Philip Sheldrake’s fears about the “SSI century”:

An acquaintance now quits those ‘old-fashioned’ relationship-building niceties and gets straight to the SSI point. Where do you work? Which college did you go to? Which college did your parents go to? Republican or Democrat? What’s your gender? Your ethnic origins? Do you have this gene or the other one?

If you fail to offer up the requisite verifiable claims then you fail to get to ‘trust building’ first base in the SSI century. (Note: this is in fact trust avoidance not trust building.) You are then ignored or indeed rejected. But it’s worse. The new social norm now expects you, expects everyone, and more accurately expects your agents to perform similar examinations as a matter of course. And why not? We’re told it’s beneficial, that it’s trust building, that it’s the missing layer. It’s frictionless. It works on an individual basis and government services have adopted it, so surely then it must be good for society as a whole?18

Data custody and security

Another major promise of this world of verifiable attestations is control over one’s own data. A common refrain is that, instead of your data being stored in Facebook’s database, or in the dusty records at the town hall, or with your doctor’s office, you can instead take your data with you.

The specifics of this vary. Some people, like Buterin, talk about recording all this data to some public blockchain or another (using various cryptographic techniques so that you’re not just blasting your personal information out to the world). Others, like McMullen, want you to use their databases. And then there are projects like Jack Dorsey’s new “Web5”, which suggests you can maintain your own “decentralized web node” with all of your credentials.

If crypto and blockchains have granted us one thing, it’s insight into how bad the average person is at securing their data. I have no great love for big banks or huge social media companies or whichever company my doctor is using to keep my medical records, but at the very least they have security teams and compliance requirements.

It’s bad enough when a person bungles their crypto wallet security practices and oops, all their apes gone. I am not optimistic about a world where someone bungles their security practices and oops, now an attacker has access to every piece of information about them, from the address of the property they’re currently living in, to their social security number, to their medical history, to their criminal record. I’m also not optimistic about a world where average people are expected to self-custody this kind of data, acting as the source of truth rather than their doctor or the town hall. I’m a software engineer and computer nerd, and I don’t trust myself to self-custody this data.

If I suddenly found myself tasked with doing so, I would probably implement some sort of expensive and technically complex system of backups, because I understand there’s no recovering from a catastrophic loss when I am the source of truth on information that is absolutely necessary for me to participate in society. I would probably become one of those crypto people that outsiders look at like they’re a bit nuts, as they hammer their private keys into blocks of steel and bury them in the backyard for safekeeping.

This is not a reasonable thing for me, a technologically-savvy software engineer who can afford a spare hard drive, to have to do. It is not a reasonable thing for anyone to have to do.

Let’s be clear: I think people should have more control over what data they provide and to whom. I think people should understand what data companies are storing, and why, and they should be able to request its removal. Sensitive data should be protected carefully, with strict limitations on who can access or share it. Penalties for unauthorized sharing or sale of user data should be severe.

But as more and more developers and companies and “blockchain visionaries” seek to eschew centralization and trust in the state and institutions, it seems that their definition of “acceptably” when they describe “acceptably non-dystopian” projects is very different from my own.

Acknowledgements

This blog post refers to the following writings and podcast episodes:

- “Soulbound: On or off Chain? | Vitalik Buterin and Evin McMullen”. Bankless, by David Hoffman. June 8, 2022. (Podcast)

- “Disco: A Digital Backpack For the LARP That Is Your Life, w/ Evin McMullen”. Digitally Rare, by Jonathan Mann and Matt Condon. March 28, 2022. (Podcast)

- Weyl, E. Glen; Ohlhaver, Puja; Buterin, Vitalik. “Decentralized Society: Finding Web3’s Soul”. May 10, 2022.

- Sheldrake, Philip. “The dystopia of self-sovereign identity”. Generative Identity. October 19, 2020.

- Guo, Eileen; Renaldi, Adi. “Deception, exploited workers, and cash handouts: How Worldcoin recruited its first half a million test users”. MIT Technology Review. April 6, 2022.

- Nieva, Richard; Sethi, Aman. “Worldcoin Promised Free Crypto If They Scanned Their Eyeballs With ‘The Orb.’ Now They Feel Robbed.”. BuzzFeed News. April 5, 2022.

Notes

-

“Sybil attack”. Wikipedia. June 10, 2022. ↩︎

-

Guo, Eileen; Renaldi, Adi. “Deception, exploited workers, and cash handouts: How Worldcoin recruited its first half a million test users”. MIT Technology Review. April 6, 2022. ↩︎ ↩︎2 ↩︎3

-

“Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) v1.0” Proposed Recommendation. W3C. August 3, 2021. ↩︎

-

“Verifiable Credentials Data Model v1.1” Recommendation. W3C. March 3, 2022. ↩︎

-

A similar trilemma, called the “Decentralized Identity Trilemma”, was proposed by Maciek Lascus in August 2018. ↩︎

-

Nieva, Richard; Sethi, Aman. “Worldcoin Promised Free Crypto If They Scanned Their Eyeballs With ‘The Orb.’ Now They Feel Robbed.”. BuzzFeed News. April 5, 2022. ↩︎

-

Zero-knowledge proofs (ZK proofs) are a strategy in which a person can prove to another person that a specific statement is true without providing additional information. For example, a person could prove that the statement “I have no outstanding unpaid debts recorded on the Ethereum blockchain” is true, without revealing to the other person the details of any past debts that might have been recorded. See “Zero-knowledge proof” on Wikipedia for more detail. ↩︎

-

zk-SNARK, or “Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge”, a type of zero-knowledge proof that doesn’t require interaction between the prover and the verifier. See “Non-interactive zero-knowledge proof” on Wikipedia for more information. ↩︎

-

“Soulbound: On or off Chain? | Vitalik Buterin and Evin McMullen”. Bankless, by David Hoffman. June 8, 2022. Quote occurs at 43:47. ↩︎

-

Bongiovanni, Ivano; Renaud, Karen, Aleisa, Noura. “The privacy paradox: we claim we care about our data, so why don’t our actions match?”. The Conversation. July 29, 2020. ↩︎

-

“Disco: A Digital Backpack For the LARP That Is Your Life, w/ Evin McMullen”. Digitally Rare, by Jonathan Mann and Matt Condon. March 28, 2022. Quote occurs at 15:37. ↩︎

-

Sheldrake, Philip. “The dystopia of self-sovereign identity”. Generative Identity. October 19, 2020. ↩︎

Disclosures for my work and writing pertaining to cryptocurrencies and web3 can be found here.